Ticks in Carlisle By Dr. Peter Burn

There are three species of human or pet biting ticks in Carlisle. As recently as twenty years ago, there was only one, and we didn’t worry much about tick-borne disease. Our only tick in those days was the dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), a potential vector of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) in humans and dogs. But RMSF is rare in Massachusetts (7 cases between 1995 and 2011, mostly on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard), and even in places where the disease is more common, only a small percentage of ticks are infected. Dog ticks are also quite large, and only adult ticks attack people, so you can generally feel them before they bite. It was a simpler time.

Within the last 20 years, we’ve added the blacklegged or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) and, most recently, the Lone Star tick (Amblyomma americanum). The Lone Star tick is a southern species, spreading to the north as the climate warms, and is not yet common. They can be vectors of several diseases including tularemia, STARI (southern tick-associated rash illness), and ehrlichiosis, which can affect both humans and dogs. They are reported to be aggressive farmacie-romania.com. We’ll need to be on the alert as they become more common.

For current disease purposes, the most dramatic change is the arrival of the deer (= blacklegged) tick. This is the vector of Lyme disease, as well as for Babesiosis, and Anaplasmosis, which are less common and less well-known but also potentially serious. It is also the primary vector of Powassan virus (usually asymptomatic but potentially fatal).

The individual deer ticks are also much more likely to carry disease than are dog ticks. Dr. Stephen Rich’s lab at UMass (http://www.tickdiseases.org/) has been testing ticks for specific diseases since 2006. Their results can be found and queried at https://www.tickreport.com/stats. During that time, nearly half (48%) of the ticks tested from Carlisle carried the Lyme disease bacterium, and 8% and 6% respectively carried Babesia and Anaplasma. This is far higher than the statewide averages for Lyme and Babesia in particular.

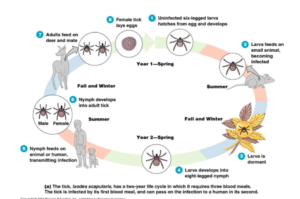

The life cycles of our three tick species are similar, but not identical. They are all so-called 3 host ticks, meaning that the larvae, nymphs and adults all attach to different hosts, typically progressively larger mammals. See Figure 1 for Ixodes scapularis as an example. It is particularly important that the first host of larval deer ticks is frequently the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), which is the most important reservoir for Lyme disease, as well as Anaplasmosis and Babesiosis. It is the mouse which serves to infect the tick with all of these diseases. Birds such as robins have been shown to be competent reservoirs, and are bitten by larval and nymphal ticks, but their role in local disease dynamics is unclear. The role of deer IS NOT to transmit the diseases, but to serve as a blood meal and dating bar for the adults, prior to laying eggs. Adult male ticks are there less to feed, more to find mates.

Figure 1 – the Ixodes Life Cycle, showing the roles of mice and deer

Deer ticks or dog ticks, whether adult or nymph, lie in lair for us or our pets in tall grass or leaf litter. One of the ways to control them is to reduce the amount of such habitats in our yards. We should also use DEET (in any insect repellent) on our skin and pant legs, and I’ve become a reluctant convert to the habit of tucking pants into my socks when working in the yard. You can also buy permethrin (an insecticide) to treat clothing and gear, such as tents. This is the product used to treat insecticidal bed nets in areas where malaria carrying mosquitos are a problem. It is not for direct application to the skin, and is highly toxic to fish. You can buy clothing (from socks to shirts to pants) treated with Permethrin, or you can treat the clothes yourself.

The bottom line is that we have ticks in town which can hurt you, and it’s only sensible to take precautions. The most dangerous tick is the deer tick, particularly the nymphs, and the most dangerous time is summer, June and July, although there is no time of year when you can let down your guard completely. Ticks in 2017 are not just a nuisance; they carry diseases which must be taken seriously.